Joaco Espagnol

Writer

Creative Director

Executive

Conveying the Essence of Motion

My creative journey started at a very young age. I used to draw my own comics when I was six years old, using printer paper and colored pencils. When I started using the internet, I moved to make comics and illustrations digitally. I would post my work online for other kids around my age to see and comment on. I received a lot of encouragement back then from these smaller art communities on websites like Neopets and DeviantART. These communities were also great places to learn from and improve my art. It gave me a great head start for pursuing my art career later on.

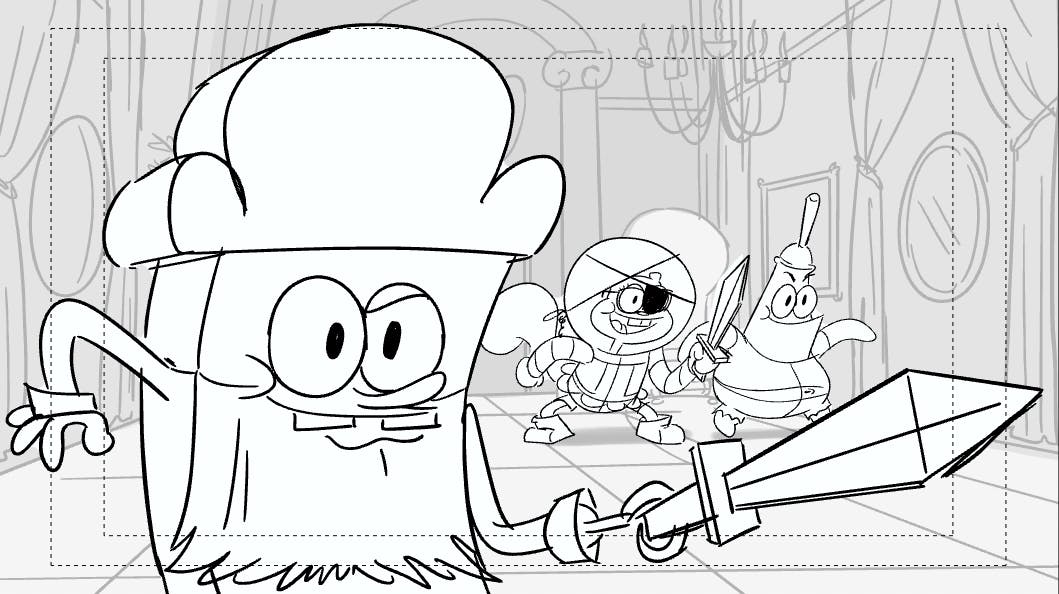

I watched a lot of cartoons as a child, and the cartoons of the 1990s and early aughts were definitely my earliest influences for my art. I really loved The Powerpuff Girls and SpongeBob. The thought of helping to make shows like those and entertaining kids like me

was definitely what led me to make the career choice that I have.

To me, communication in storyboards should always come before being visually evocative. The most impressive shots are the ones that use interesting visuals to communicate the story; otherwise, people are too busy trying to figure out what’s happening to even appreciate your choices, no matter how impressive they are. When thinking about whether to use a certain shot, the first thing I always ask myself is if that choice helps to communicate the story. From there, I can choose the shot that is the most visually interesting to me, so long as it’s helping the story and not hurting it.

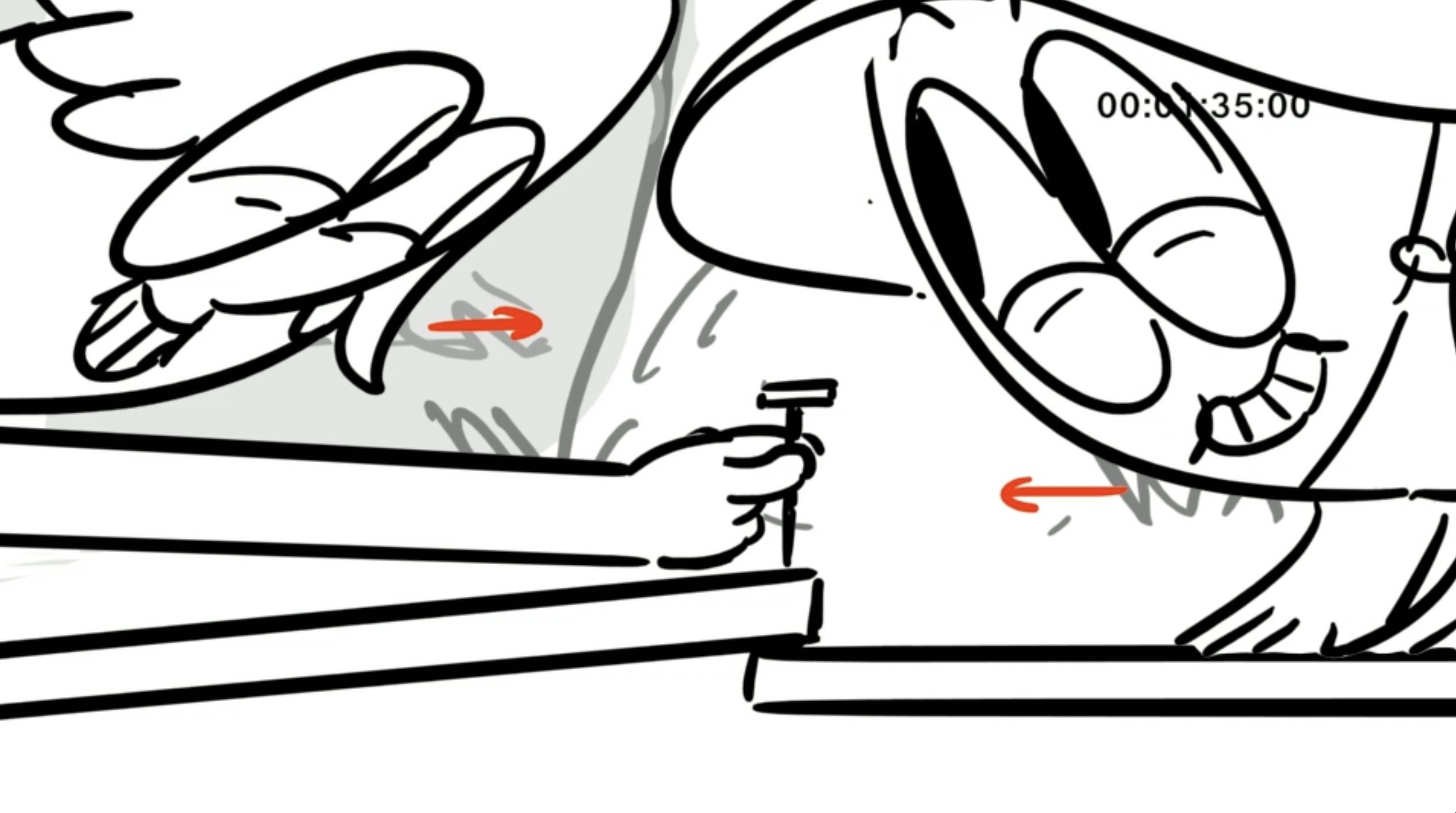

For making personal storyboards, my process isn’t very different from working on boards for productions, probably because I did most of my learning while on the job. I start with drawing thumbnails, then do two or three passes on a final board, just like I do for a job. When I make personal animation work, I would say I’m looser in my process than I am for client projects. In my animations, I feel freer to be as rough as I want with my first animation pass, knowing that I won’t have to show it to anyone or try to explain what’s happening to anyone but myself.

This depends on the show. Some shows want board artists to draw on models, while others don’t mind if you draw in your style. I’ve been on both types of shows; getting to draw in my style is definitely more fun for me. I figure, much like drawing itself, my style of storyboarding probably comes through subconsciously. It’s hard to describe how I’ve gotten to the place that I have.

From the very beginning, my artistic pursuit has been fuelled by a relentless quest for expressiveness. Captivated by the art of bringing faces and bodies to life, I pour my passion into creating evocative and three-dimensional renditions in my personal work.

I don’t do a whole lot of life drawing now, but it’s an important skill to practice at least once in a while. I always try to go to a figure-drawing event if I can. Working from life always helps if I feel like my drawing skills are rusty, which can happen if I take a long break for whatever reason. Working from your imagination is important too. When I’m sketching from my imagination, I’m honing my ability to be creative and come up with fun ideas. So, to me, both are necessary for the work I do.

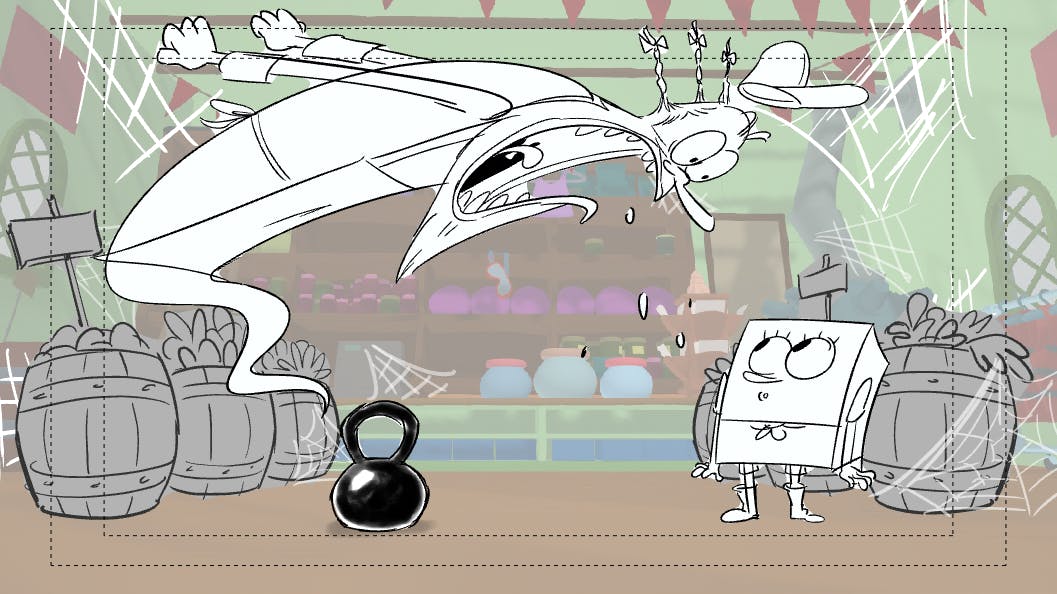

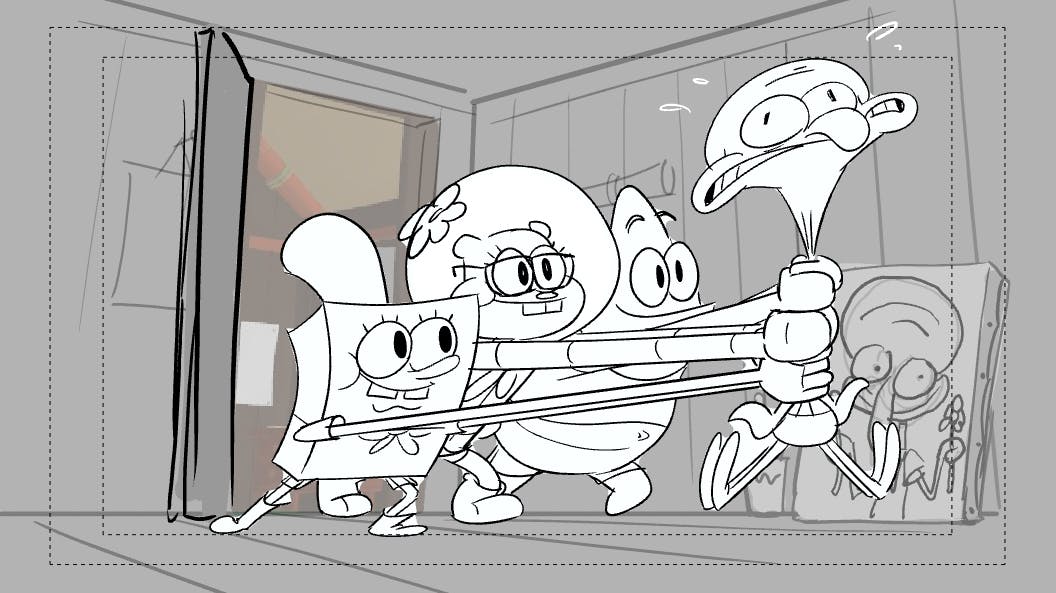

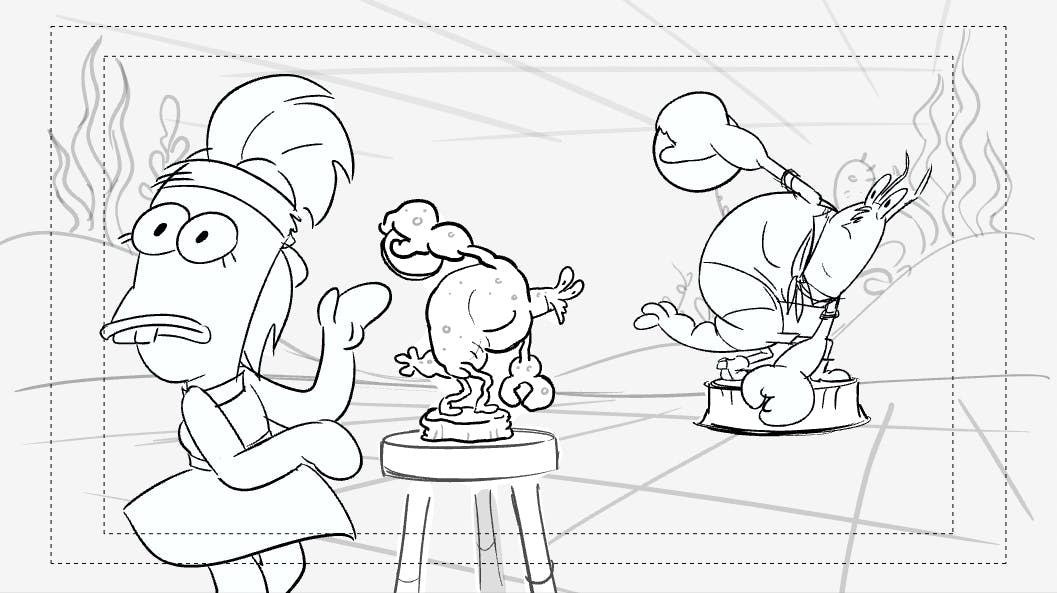

Storyboarding presents a unique challenge as it requires conveying the essence of motion with a limited number of drawings compared to a fully animated project. When working on expressive and cartoony scenes, I often push the boundaries of my drawings to amplify their impact beyond what I would typically do for animation. The goal is to effectively communicate the scene's narrative, and sometimes an illustration that may appear "correct" in animation can be perplexing in a storyboard context. As a result, I find myself making unconventional choices that diverge from the norm of animation.

I sometimes do, though not as often as I would have expected. Part of it is that I’m drawing these boards and not seeing the final product until well over a year later, so I tend to forget many of the choices I made at the time. But I think a huge part of making stuff for TV is that it’s a collaboration with other very talented people, and something is exciting about recognizing when someone later on in the pipeline builds on something that I did, whether it’s a board revisionist who added a funny gag to a scene I boarded, or a designer who put some fun easter eggs in the very simple background I drew, or an animator who added some wonderful embellishments to the character animation I did a few poses for. At the end of the day, it takes multiple artists who are great at what they do to get the final product to be the best it can be.

The only way to get good at something is to study and practice. Be specific about what drawing skills you want to improve on. Do you want to learn how to draw more expressive poses? Do you want to get better at staging? Then find an artist whose work achieves that and figure out what they’re doing that makes them successful at it. There are so many great art resources on the internet that can help you improve at just about anything. It can be a bit overwhelming, but setting smaller goals will help you improve at drawing overall. And be kind to yourself on that journey, because usually when you’re most critical of your art, you’re making the most improvements.